« PREVIOUS ENTRY

Come for the design, stay for the text

NEXT ENTRY »

Hacking the Model T

“How did you find my site?”

I get asked this question a lot. Whenever I call up someone to interview them — because I’ve read their scientific paper or their blog posting or looked at their company online — they inevitably ask me a variant of that question. (“How’d you find my paper? My company?” etc.) It’s a natural thing to wonder about.

The problem is, I often can’t answer it.

If I’ve heard about the interviewee via a recommendation from a friend, or via a story I read in, say, the Wall Street Journal, then sure, I can usually remember how I found them. But at least 50% of the time I encountered their work during online surfing …

… and this is where my trouble begins. Because the truth is, while I love finding cool things online, it’s often incredibly hard to reconstruct precisely how I stumbled across them. This is why I’ve always thought the corporate name for StumbleUpon is so brilliant: The process of finding something really does feel like stumbling. You careen about digressively, following intuitions, doing a couple of searches, getting distracted (destructively and productively), when suddenly — wham — you discover you’re reading something that is zomg awesome. You follow a link in page A that mentions post B that ports to tweet C that is from person D who posted on their personal site about E.

But later on, it’s damn hard to recall precisely how A led to E. You could look at your web history, but it’s an imprecise tool. If you happened to have a lot of tabs open and were multitasking — checking a bit of web mail, poking around intermittently on Wikipedia — then the chronological structure of a web “history” doesn’t work. That’s because there’ll be lots of noise: You’ll also have visited sites G, M, R, L, and Y while doing your A to E march, and those will get inserted inside the chronology. (Your history will look like A-G-B-M-R-C-D-L-Y-E.) Worse, often it’s not until days or weeks after I’ve found a site that I’ll wonder precisely how I found it … at which point the forensic trail in a web history is awfully old, if not deleted.

But hey: Why does this matter? Apart from pecuniary interest, why would anyone care about the process by which you found a cool site?

Because there’s a ton of interesting cognitive value in knowing the pathway.

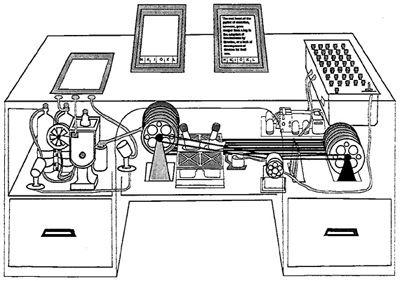

If you’re reading this blog, you are probably least part nerd, which means you’ve likely read (or have heard of) Vannevar Bush’s 1945 essay for the Atlantic Monthly, “As We May Think”. Bush’s essay has become famous amongst digital folks because of how eerily he predicted the emergence of a hyperlinked Internet. “As We May Think” is, at heart, a complaint about information overload (in 1945!) and a suggestion of how to solve it: By building better tools for sorting, saving, and navigating stuff. Bush envisioned a “memex”, a desk-like tool at which you’d sit, reading over zillions of documents stored via microfilm. You could also write your own notes and reflections (which would saved in microfilm format too, photographed automatically via a forehead-mounted webcam “a little larger than a walnut”. That illustration above is a rough mockup of a Memex, by the way.)

The really Nostradamusian element, though, was the hyperlinks. An essential part of the memex, Bush envisioned, would be its system for letting you inscribe connections between documents. He described someone doing research into the history of the “Turkish bow”: The user pores over “dozens of possibly pertinent books and articles”, finds one particularly useful one, then another, and “ties the two together”. He continues on, adding in his own “longhand” notes, and eventually he “builds a trail of his interest through the maze of materials available to him.”

This is, of course, precisely how one does research online today. Except for one big difference: We don’t really have tools for saving what Bush calls the “trail” — the specific pathway by which someone went from one document to another. Sure, we share the results of our online surfing. We do that all the time: Links posted to Twitter, Facebook, a gazillion public fora. But when someone asks “how’d you find that? What was your pathway?”, we often don’t know. We share the results of our knowledge formation, but not how we formed it.

Yet when you read “As We May Think”, Bush clearly thought there was enormous value in sharing the trail. He talks about that specifically in the case of the Turkish bow example, and then describes a few others, too:

And his trails do not fade. Several years later, his talk with a friend turns to the queer ways in which a people resist innovations, even of vital interest. He has an example, in the fact that the outraged Europeans still failed to adopt the Turkish bow. In fact he has a trail on it. A touch brings up the code book. Tapping a few keys projects the head of the trail. A lever runs through it at will, stopping at interesting items, going off on side excursions. It is an interesting trail, pertinent to the discussion. So he sets a reproducer in action, photographs the whole trail out, and passes it to his friend for insertion in his own memex, there to be linked into the more general trail.

Wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready made with a mesh of associative trails running through them, ready to be dropped into the memex and there amplified. The lawyer has at his touch the associated opinions and decisions of his whole experience, and of the experience of friends and authorities. The patent attorney has on call the millions of issued patents, with familiar trails to every point of his client’s interest. The physician, puzzled by a patient’s reactions, strikes the trail established in studying an earlier similar case, and runs rapidly through analogous case histories, with side references to the classics for the pertinent anatomy and histology. The chemist, struggling with the synthesis of an organic compound, has all the chemical literature before him in his laboratory, with trails following the analogies of compounds, and side trails to their physical and chemical behavior.

The historian, with a vast chronological account of a people, parallels it with a skip trail which stops only on the salient items, and can follow at any time contemporary trails which lead him all over civilization at a particular epoch. There is a new profession of trail blazers, those who find delight in the task of establishing useful trails through the enormous mass of the common record. The inheritance from the master becomes, not only his additions to the world’s record, but for his disciples the entire scaffolding by which they were erected.

The entire scaffolding by which they were erected: I love that phrase. What Bush is talking about here, I’d argue, is metacognition: Thinking about thinking, knowledge about the way we make knowledge. He understood that knowing how someone thinks and searches and finds is as valuable as the the things they’ve actually found.

Our society doesn’t have a lot of tools for sharing thought processes. Scholars and scientists have developed some, in academic papers: They have formal requirements to “show their work” and talk through how they’ve come to a new conclusion. And of course, a well-written nonfiction argument talks you through evidence in a way that’s a bit similar. But in the modern age, though, one could imagine everyday tools would help us peel back the mystery of our online searching, finding, and thinking. I’d love to have a tool that represented my web history in a more semantically or graphically rich way — clustering individual things I was reading by their “trail”, to use Bush’s term. And I’d love to be able to share that with someone else — and see their trails, too.

Indeed, we clearly have an appetite for knowing how and where people found stuff. Every time someone creates a new tool for publishing online — blogs, status updates, social networks, you name it — users on a grassroots level immediately create conventions for elaborately backlinking and @crediting where they got stuff from. It’s partly reputational, but it also betrays the fact that we seriously enjoy associational thinking and finding.

Now, It’s quite likely that such a “trail” tool exists and I simply don’t know of it. Anyone out there seen something that does this? The closest I’ve seen is the “Footprints” experiment from 1999 by Alan Wexelblat and Pattie Maes … and even it wasn’t quite what Vannevar Bush was envisioning. (As I recall, Ted Nelson’s Xanadu project was quite interested in this sort of “trail” recording too … another reason why it’s sad it never took off.)

At any rate, the reason this subject is on my mind today is that I saw the New York Times story about the two Youtube founders preparing to revamp and relaunch Delicious. Though Delicious had long been left to moulder by Yahoo, and its basic genius — letting you publicly bookmark things you’ve found online — has been superseded by newer services like Diigo, I’ve often felt Delicious comes closest to evoking the trail of people’s mental associations as they find things online. Indeed, one of my favorite things is to save a bookmark on Delicious, and then check to see how many other people have bookmarked it. If several hundred have done so, that’s somewhat interesting; I know the site is popular. But if the site has been only bookmarked by only three or four other people — out of Delicious’ five-million-plus user base — then I know something much more interesting: That those two or three other people and I share some strange, oddball intellectual overlap. So I’ll inevitably bounce over and look at all of their bookmarks, and it feels like getting a very slight glimpse, in a Bushian sense, of the way they think. (For example, a few days ago I bookmarked this academic study of how online and offline teaching styles compare, and saw that only four other people had saved it. One of those users was “Sue Folley”, who, as you might suspect, had saved a ton of stuff about education … but also this fascinating post about why it’s hard to think of a question during the Q&A period after a lecture. I think I’ve probably generated a half-dozen Wired columns purely by perusing the mind-map someone else has autogenerated for me online.)

Anyway, when I read the New York Times piece I grew faintly hopeful that the Youtube guys will push Delicious in a vaguely “As We May Think” direction. As the story noted:

But the new Delicious aims to be more of a destination, a place where users can go to see the most recent links shared around topical events, like the Texas wildfires or the anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks, as well as the gadget reviews and tech tips.

The home page would feature browseable “stacks,” or collections of related images, videos and links shared around topical events. The site would also make personalized recommendations for users, based on their sharing habits. “We want to simplify things visually, mainstream the product and make it easier for people to understand what they’re doing,” Mr. Hurley said.

Mr. Chen gives the example of trying to find information about how to repair a vintage car radio or plan an exotic vacation.

“You’re Googling around and have eight to 10 browser tabs of results, links to forums and message boards, all related to your search,” he said. The new Delicious, he said, provides “a very easy way to save those links in a collection that someone else can browse.”

If you added some sense of chronology-of-discovery to those “collections”, you’d have something approaching Bush’s “trails”.

UPDATE! Cory Doctorow posted about the entry on Boing Boing, and in the comments, people listed several web tools that approximate the Vannevar Bush idea of “trails”. Some of the ones listed:

- “Pathways”: this one produces a map of pages as you go through Wikipedia. It’s Mac only, and I’m not sure if it currently works.

- “How’d I get here?”: A plug-in for Firefox, which sadly now appears to be defunct, but which would show you the page on which you first clicked a link to the page you’re currently on.

- “Tab History Redux”: another Firefox plug-in — Open new tab, and it’ll save a record of which link it came from.

- “Voyage”: this is the closest one yet! A Firefox plug-in that displays pathways of your surfing as visual maps. Not sure it still works though.

- “Wikipedia contrails”: Matt Webb posted about his project in which he would list Wikipedia pages, manually, as he went through them — the Wikipedia “contrail”. Very fun! Not automated though.

I'm Clive Thompson, the author of Smarter Than You Think: How Technology is Changing Our Minds for the Better (Penguin Press). You can order the book now at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Powells, Indiebound, or through your local bookstore! I'm also a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and a columnist for Wired magazine. Email is here or ping me via the antiquated form of AOL IM (pomeranian99).

ECHO

Erik Weissengruber

Vespaboy

Terri Senft

Tom Igoe

El Rey Del Art

Morgan Noel

Maura Johnston

Cori Eckert

Heather Gold

Andrew Hearst

Chris Allbritton

Bret Dawson

Michele Tepper

Sharyn November

Gail Jaitin

Barnaby Marshall

Frankly, I'd Rather Not

The Shifted Librarian

Ryan Bigge

Nick Denton

Howard Sherman's Nuggets

Serial Deviant

Ellen McDermott

Jeff Liu

Marc Kelsey

Chris Shieh

Iron Monkey

Diversions

Rob Toole

Donut Rock City

Ross Judson

Idle Words

J-Walk Blog

The Antic Muse

Tribblescape

Little Things

Jeff Heer

Abstract Dynamics

Snark Market

Plastic Bag

Sensory Impact

Incoming Signals

MemeFirst

MemoryCard

Majikthise

Ludonauts

Boing Boing

Slashdot

Atrios

Smart Mobs

Plastic

Ludology.org

The Feature

Gizmodo

game girl

Mindjack

Techdirt Wireless News

Corante Gaming blog

Corante Social Software blog

ECHO

SciTech Daily

Arts and Letters Daily

Textually.org

BlogPulse

Robots.net

Alan Reiter's Wireless Data Weblog

Brad DeLong

Viral Marketing Blog

Gameblogs

Slashdot Games