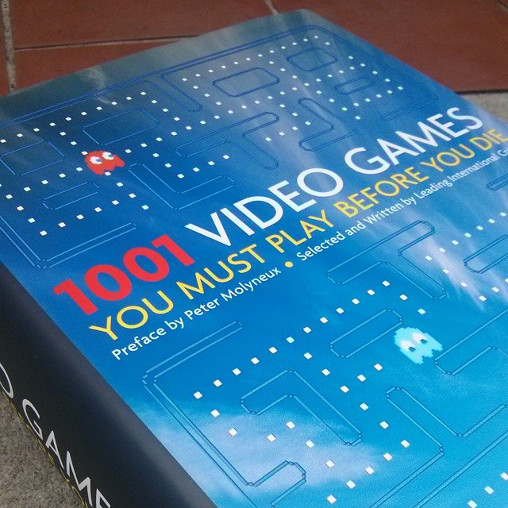

I recently picked up 1001 Video Games You Must Play Before You Die. I couldn’t resist the title, which so neatly refracts the gibbering cultural anxieties of lists like “1000 novels everyone must read”. You see this sort of highbrow listicle often in the realms of literary fiction, movies, possibly poetry. It’s classic canon panic, and I say that with a degree of charity and warmth; I actually think arguing heatedly and even snobbishly about what works of art are important and mindbending can be a lot of fun, and occasionally useful to the parties involved.

But there’s something hilarious and unsettling about claiming there are 1,001 video games we must play. On the obvious level, it’s a cheeky way of mocking the way literary fiction — or perhaps movies — are the only arts that self-aggrandizingly proclaim themselves highbrow enough to be considered absolutely compulsory for all non-knuckle-dragging hominids. On a subtler level, it throws a challenge even to gamers themselves. It suggests that no matter how many titles they’ve played and enjoyed (or hated), there is a much, much larger sea out there. Indeed, the idea that there is a subset of games that are mandatory, and that this number is as large as 1,001, points to the fact that the pool of nonmandatory games (the bad ones, the forgettable ones, the aesthetically and game-mechanically uninspired ones) is probably several orders of magnitude bigger — tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands of games. Maybe more?

I mean, how many video games have been made, anyway? I’ve never seen a good estimate of this. When you throw in disposable app-store games — the phyloplankton of the game world, some so forgettable you’d swear they’d just been procedurally generated (and come to think of that, that would make a crazy project! A robotic game studio that craps out algorithmically-generated games, much like the programmers who bulk-spray thousands of algorithmically-generated books onto Amazon) — the number becomes Carl-Sagan huge.

Could anyone actually play 1,001 games? Let’s do the math! Since modern games promise, in general, “40 hours of play”, we’re talking about 40,000 hours of play. Actually, let’s shrink that down to 30,000 hours, because many early arcade games discussed in this book could be “played through” in a few minutes or an hour or so. But even at 30,000 hours, that’s 14 solid years of playing, if you took it on as a full-time job, played for 40 hours a week, and tried to get to the end of every game.

The upshot is, the whole sly point of a book like 1001 Video Games You Must Play Before You Die is that you’re really never going to be able to play them all. The fun is in reading about them — in touring through the encyclopedic entries.

In this regard, I gotta say, the book does not disappoint. The writeups are all barely a villanelle’s-worth in length — a single short page, or even half a page — yet the writers (about two dozen game journalists) manage to fit in a number of really delightful observations.

Which brings me to the whole reason I’m writing this post! In the writeup for Half-Life 2, Duncan Harris makes a fascinating argument about the title. I’ll quote nearly the whole writeup:

Released in 2004 after five years in development, it continues the story of an alpha geek, scientist Gordon Freeman, as he deals with the aftermath of an experiment gone wrong. Placed back on Earth by the mysterious G-Man, he finds himself entering City 17, the cold and forbidding capital of the world now enslaved by aliens. The Combine, who snuck into our dimension, thanks to the events of Half-Life, have broken humanity’s spirit and turned it cities into ghettos. Citizens wear rags and huddle next to tenement windows, waiting for the Civil Protection squads to abduct them to who-knows-where. There are no children.

Had the game been so vulgar as to mimic any movies, there’d have been a Hollywood version years ago. But the secret of it success is that, while full of historical parallels, it tells its story as if games were the only medium on Earth. There are no cut scenes, no paragraphs of exposition to read, and the closest you’ll get to pop-culture references are Orwell and H.G. Wells. In their place, Valve’s artists, technicians, storytellers, and sound engineers create a unique milieu: a distinctly Soviet metropolis being literally consumed by alien architecture.

It tells its story as if games were the only medium on Earth. That is a really great observation, even if it’s not true, and I’m not sure it is. (Among other things, the story, characters and dialogue are pretty straightforwardly modeled on the tropes of action flicks.) But the gist of the point — that what makes a game interesting is its desire to be gamelike, to take its reference points from other games, to regard gameness as central — is nicely put.

This is one of the reasons I’ve always dug third-person video games. Their camera aesthetics are totally weird and utterly game-like. When you play, you’re almost always constantly staring at the back of your character, as you guide it around the world, as per last year’s Tomb Raider, an early pioneer in the third-person perspective back in the 90s:

This is a camera technique born of pure functionality: As a player, you need to be seeing the world in front of your character, so the camera-view must always be floating just behind the character, as if you were a spirit anxiously accompanying your creation. And of course when your character is in tight quarters, like a hallway, the “floating behind” camera view gets all screwed up, with the camera often getting stuck behind objects or appearing to float inside walls.

The thing is, the third-person game camera-angle is truly and totally foreign to Hollywood. I can’t imagine any director saying “guys, guys! I’ve got a great idea! Let’s shoot our entire movie from about five feet behind behind the protagonist, carefully tracking behind her, so that we almost never see her face!” That third-person angle is a piece of artistry that is utterly gamelike — a bit of aesthetics crafted as if games were, indeed, the only medium on Earth.

I'm Clive Thompson, the author of Smarter Than You Think: How Technology is Changing Our Minds for the Better (Penguin Press). You can order the book now at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Powells, Indiebound, or through your local bookstore! I'm also a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and a columnist for Wired magazine. Email is here or ping me via the antiquated form of AOL IM (pomeranian99).

ECHO

Erik Weissengruber

Vespaboy

Terri Senft

Tom Igoe

El Rey Del Art

Morgan Noel

Maura Johnston

Cori Eckert

Heather Gold

Andrew Hearst

Chris Allbritton

Bret Dawson

Michele Tepper

Sharyn November

Gail Jaitin

Barnaby Marshall

Frankly, I'd Rather Not

The Shifted Librarian

Ryan Bigge

Nick Denton

Howard Sherman's Nuggets

Serial Deviant

Ellen McDermott

Jeff Liu

Marc Kelsey

Chris Shieh

Iron Monkey

Diversions

Rob Toole

Donut Rock City

Ross Judson

Idle Words

J-Walk Blog

The Antic Muse

Tribblescape

Little Things

Jeff Heer

Abstract Dynamics

Snark Market

Plastic Bag

Sensory Impact

Incoming Signals

MemeFirst

MemoryCard

Majikthise

Ludonauts

Boing Boing

Slashdot

Atrios

Smart Mobs

Plastic

Ludology.org

The Feature

Gizmodo

game girl

Mindjack

Techdirt Wireless News

Corante Gaming blog

Corante Social Software blog

ECHO

SciTech Daily

Arts and Letters Daily

Textually.org

BlogPulse

Robots.net

Alan Reiter's Wireless Data Weblog

Brad DeLong

Viral Marketing Blog

Gameblogs

Slashdot Games